SOLID principles: The Open-Closed Principle (Part II)

SOLID principles tell you how to arrange your functions into classes and how those classes should be interrelated.

When SOLID principles are applied correctly, your software infrastructure will be able to tolerate changes, it will be easier to understand, and it will be focuser on reusable components.

After reviewing the Single Responsibility Principle included in the SOLID principles, let’s proceed to the second principle.

SOLID principles: The Open-Closed Principle (OCP)

… “a module, class, or function should be open for extension but closed for modification.“

Bertrand Meyer coined the principle, suggesting that we should build software to be extendable without touching its current code implementation.

But there are situations we change one of our classes, and we realize that we need to adapt all its depending classes.

Explaining the Open-Closed Principle with code examples

For instance, imagine that we are assigned the task of How to implement Rate Limiting algorithm to control the number of requests allowed for every endpoint in a REST API.

The RateLimit class implements an interceptor - HandlerInterceptor - that allows an application to intercept HTTP requests before they reach the service, so we can either let the request go through or block it and send back the status code 429.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

public class RateLimit implements HandlerInterceptor {

private Map<String, Long> apiPlans;

@Override

public boolean preHandle(HttpServletRequest request,

HttpServletResponse response, Object handler) throws Exception {

//getClientId

apiPlans = getAPIPlans();

//build Buckets

//evaluate request per clientId

//accept(200) or refuse(429) request

}

}

The number of requests allowed during a time interval is specified in plans; for example, plan A allows to consume 100 requests in 1 minute.

The team wants to retrieve the number of requests by plan from a text file. The following getAPIPlans method retrieves those parameters.

The following getAPIPlans method retrieves those parameters.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

private Map<String, Long> getAPIPlans() throws Exception {

Map<String, Long> apiPlans = new ConcurrentHashMap<>();

Resource resource = new ClassPathResource("apiPlans.txt");

try {

List<String> allLines = Files.readAllLines(Paths.get(resource.getURI()));

for (String line: allLines) {

String[] attributes = line.split(":");

String plan = attributes[0];

long capacity = Long.valueOf(attributes[1]).longValue();

apiPlans.put(plan, capacity);

}

} catch (IOException e) {

throw new RuntimeException(e.getMessage());

}

return apiPlans;

}

When suddenly, an unexpected scenario arises

The developer leaves the company, and a new one arrives—for example, You.

As developers, we usually receive tasks to do maintenance in projects that do not belong to us; specifically, we never created that code.

Then weeks later, your team decides that must be retrieved parameters from a database. Therefore you proceed to replace the getAPIPlans method; then, you break the open-closed principle.

That is the meaning of the principle; you can not touch the code that is already implemented and working for a long time. Suppose the code is too complex to understand, not well documented, and includes a lot of dependencies. In that case, we have a lot of probabilities to introduce a bug or break some functionalities that we cannot visualize. Unless it is a bug that we have to fix, we should never modify the existing code.

Even if the code is not well designed or does not follow object-oriented programming concepts, it could not be easy to extend a class to introduce new functionalities.

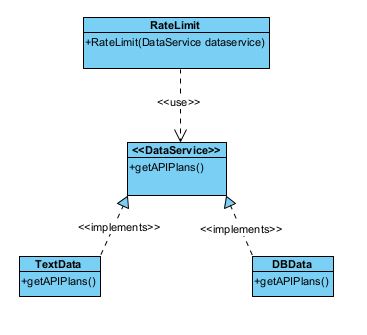

The team wants to implement the open-closed principle to support future changes for this scenario. But they need to adopt Refactoring techniques to promote the Open-Closed Principle. For this scenario: polymorphism and aggregation.

Polymorphism

Polymorphism is part of the core concepts of Object-Oriented Programming and means many forms, allowing an object to behave differently in some instances. For our scenario, polymorphism will enable the getAPIPlans method to achieve its goals in different ways: retrieve the parameters from a text file or a database.

Aggregation

Aggregation defines a HAS-A relationship between two classes. Their objects have their life cycle, but one of them is the owner of the HAS-A relationship.

The following diagram shows the goal of our design.

Please donate to maintain and improve this website if you find this content valuable.

Read more about Understanding OOP concepts.

Achieving extensibility with the Open-Closed Principle

Firstly, and thinking abstractly, you should create an interface and define a contract that will include all required functionalities.

1

2

3

4

5

public interface DataService {

public Map<String, Long> getAPIPlans() throws Exception;

}

Secondly, we move our getAPIPlans method to a new class that implements the previous interface.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

public class TextData implements DataService {

@Override

public Map<String, Long> getAPIPlans() throws Exception {

Map<String, Long> apiPlans = new ConcurrentHashMap<>();

//code omitted for brevity

return apiPlans;

}

}

Thanks to abstractions, we can create a new class to implement getAPIPlans with different behavior, in this case, to retrieve parameters from a database.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

public class DBData implements DataService {

private DataSource datasource;

public DBData(DataSource datasource) {

this.datasource = datasource;

}

@Override

public Map<String, Long> getAPIPlans() throws Exception {

Map<String, Long> apiPlans = new ConcurrentHashMap<>();

for (Plan plan : datasource.getAPIPlans()) {

//code omitted for brevity

}

return apiPlans;

}

}

Introducing a new abstraction layer with different implementations avoids tight coupling between classes.

Finally, we refactor our RateLimit class aggregating an instance of DataService type in its constructor method.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

public class RateLimit implements HandlerInterceptor {

private Map<String, Long> apiPlans;

private DataService dataService;

public RateLimit(DataService dataService) {

this.dataService = dataService;

}

@Override

public boolean preHandle(HttpServletRequest request,

HttpServletResponse response, Object handler) throws Exception {

//getClientId

apiPlans = dataService.getAPIPlans();

//build Buckets

//evaluate request per clientId

//accept(200) or refuse(429) request

}

}

If later we decided to retrieve the parameters from a NoSQL database such as Elasticsearch, we would no longer have to touch the code, create a new class that implements getAPIPlans, and instantiate this new class in RateLimit.

Even if, instead of implementing the HandlerInterceptor interface, we implement a Filter to design our Rate Limit algorithm, we can reuse the DataService interface as one of its dependencies.

Calling to getAPIPlans is now fixed (closed for modification). If we want it to behave differently, we implement it in a new class (open for extension) that will follow the contracts defined in our interface.

Our new DBData dependency is instantiated in our RateLimit class thanks to the magic of the Dependency Injection principle, which I will explain in a near-future article, so follow me!.

Applying these Refactoring techniques, the Open-Closed Principle enhances software maintainability.

Do you want to know more about Software Design Principles?

Here’s a Quick Guide to Elevate Your Projects with Proven Software Design Tactics!. – Software Design Principles